|

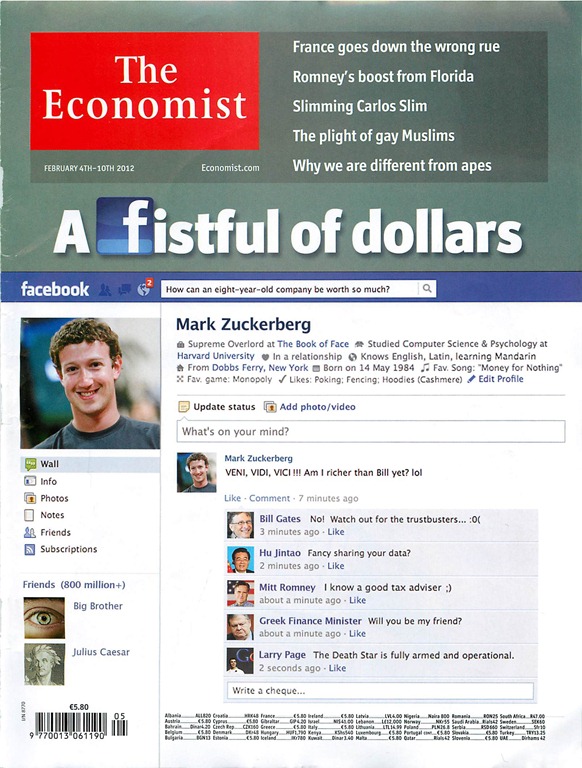

| I contend that this remains The Economist's most brilliant cover. It's from 2012, when Facebook shares were made public. |

I elected to deactivate my Facebook account yesterday. According to Facebook, deletion is a 30-day process and I suppose that means I can be found on there until the end of July. It's a little sad, as I'll miss the way in which the program allowed me to connect with people I ordinarily don't get to see. There are some friends who will miss seeing what I post, though I've become much more passive on that platform in the last year or so.

That being said, I am in contact with the people who mean the most to me in many other reliable ways. The real cost here, it seems, are those chance meet-ups that may have occurred via Facebook over the next few years. So there are two or three voices and faces from the distant past I'll miss out on seeing. And that's a shame.

Are there political reasons for my decision to deactivate my account? Yes. It's 2020, after all, and it seems anything we do has political overtones. Going into all that doesn't seem like a good use of time right now.

I will share with you now, though, that for me Facebook had simply ceased to be fun. It didn't bring me joy, but instead the angst as if walking on eggshells. Part of this is political. A more important reason why Facebook was becoming joyless, though, stems from my role as a teacher. A cost of choosing that vocation is that I must be more careful about what I say and represent for a whole host of reasons (ethical, legal, professional).

So, I'll keep writing here. And I'll lean more heavily on some platforms that have proven less joyless and more useful the past few weeks (Zoom, Teams, and Facetime come to mind). I still actually like email. On this pessimistic weekend, I need to remind myself that we have tools that allow me to stay in touch, even though I've turned one of them off.