|

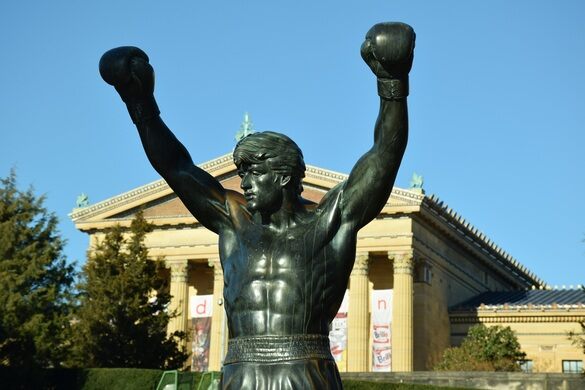

| A statue that might be less controversial now than when it was first put up. |

Really, only legal niceties are in the way of them coming down. For instance, the removal of the Lee statue from Monument Avenue in Richmond is suspended over language about the deed or the will by which the state of Virginia got access to the parcel on which the statue is perched.

Perhaps I should pause, though, on this legal nicety thing. Deferring to the courts has become a bit too common in America and the impulse to have everything tied up in the land of judgments, injunctions, and appeals is a significant problem right now. We've fallen out of the practice of legislating in America. We've fallen more horribly out of the practice of compromising. So as ideas to move society forward or backward are stalled in legislatures between uncompromising parties, we increasingly appeal to courts, hoping they'll take our side. John Stewart, in a recent interview for New York Times Magazine, likened this phenomenon to Americans complaining to management as a way of making law.

The courts' role in complicating this moment aside, we are at an interesting moment. A moment in which the public display of artifacts relevant to the Confederacy are becoming widely unacceptable. Those supporting those displays are maybe even conceding defeat. But the argument is moving now to monuments and statues representing more obliquely difficult memories from our past.

A recommendation: There's a great article from a art critic and journalist regarding statues such as the Theodore Roosevelt statue in New York. It's worth a read.

As Americans debate these statues, it's worth considering the context of when those statues were erected. A statue of Christopher Columbus wasn't raised in 1500, but instead centuries later. Why was it put up then? Who was sponsoring it? The statue of Frank Rizzo recently taken down in Philadelphia wasn't put up while he was mayor, or even when he was alive. Instead it was put up in the late 1990s. Why then?

Statues are symbols and expressions. And we're living in a time where what symbols and expressions are fluid, charged, and sometimes contradictory. Memes and hashtags are an increasingly important element of dynamic conversation today. We might be readier to appreciate the context of why statues went up now than we were just a few decades ago.

Keep in mind that much of what damns the Confederate statues is the timing of their installation and dedication.

Keep in mind, also, that there is tremendous disjointure of time between the deed, the statue, and today. There are many moral contexts in which these statues are set (three really). Allowing them to remain is a moral statement. When they went up is a moral statement. And those moral statements might matter more than the deeds and the time in which they occurred.

***

I began this post with a photo of Philadelphia's least controversial statue, the Rocky statue at the steps of the Art Museum. Most would consider it quite benign today, and I think that's appropriate. However, it was erected in the early 1980s memorializing a film character made famous in 1976. One can do a little digging to learn that contemporary critics of the film Rocky found quite an edgy racist undercurrent to the film. It's an interpretation that in the context of mid-1970s America carries quite a bit of validity. But the validity of the argument is undermined by each sequel of the franchise. It's hard now to see the Rocky franchise as a racial statement today. Perhaps it's possible for a statue to become less controversial over time.

Or maybe that's just in Hollywood.

No comments:

Post a Comment